Summer Evaluation Series - Real-life example in the Science of Reading!

Happy Summer 2025!

I am happy to introduce my summer blog series on project evaluation - this is post 1 of 3.

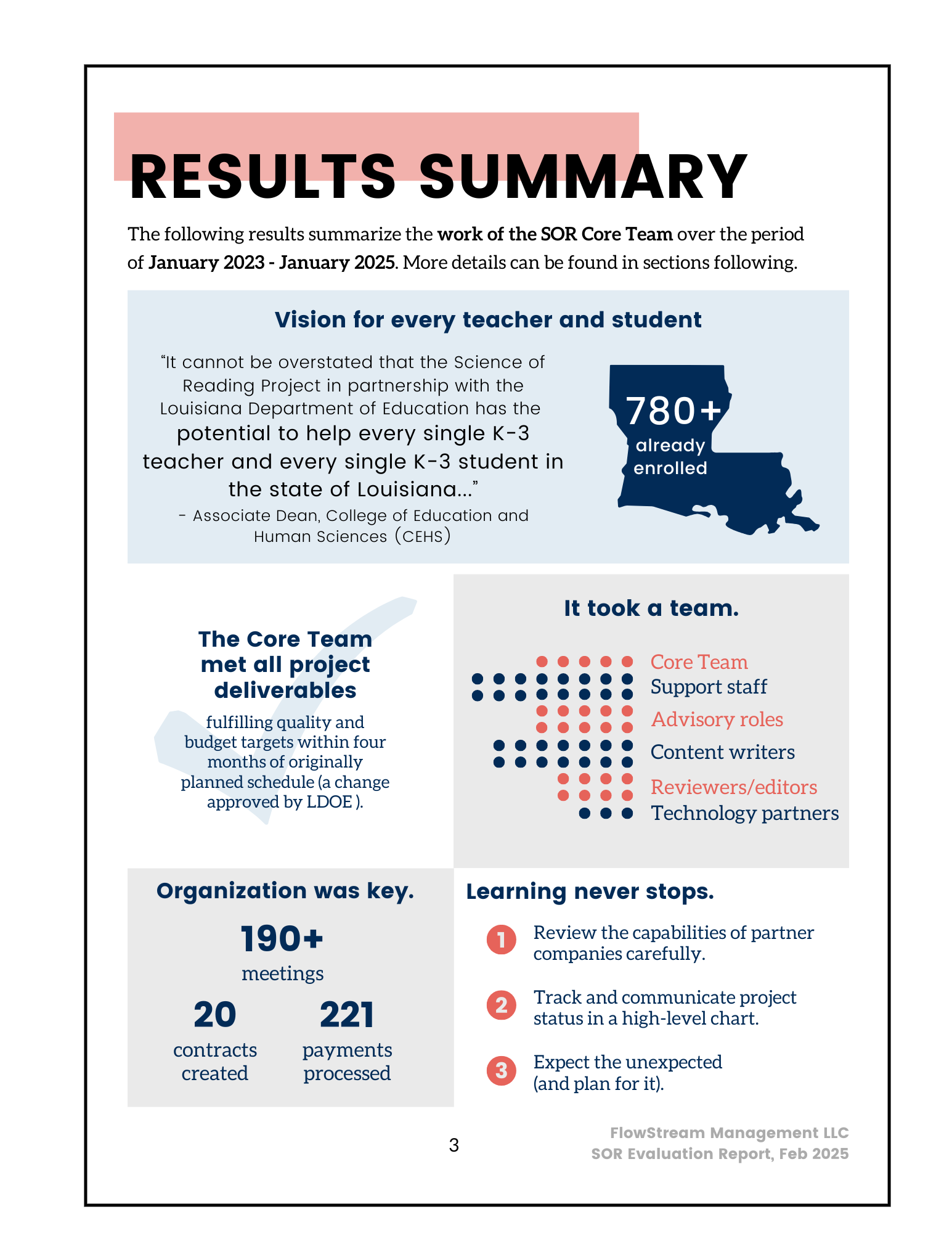

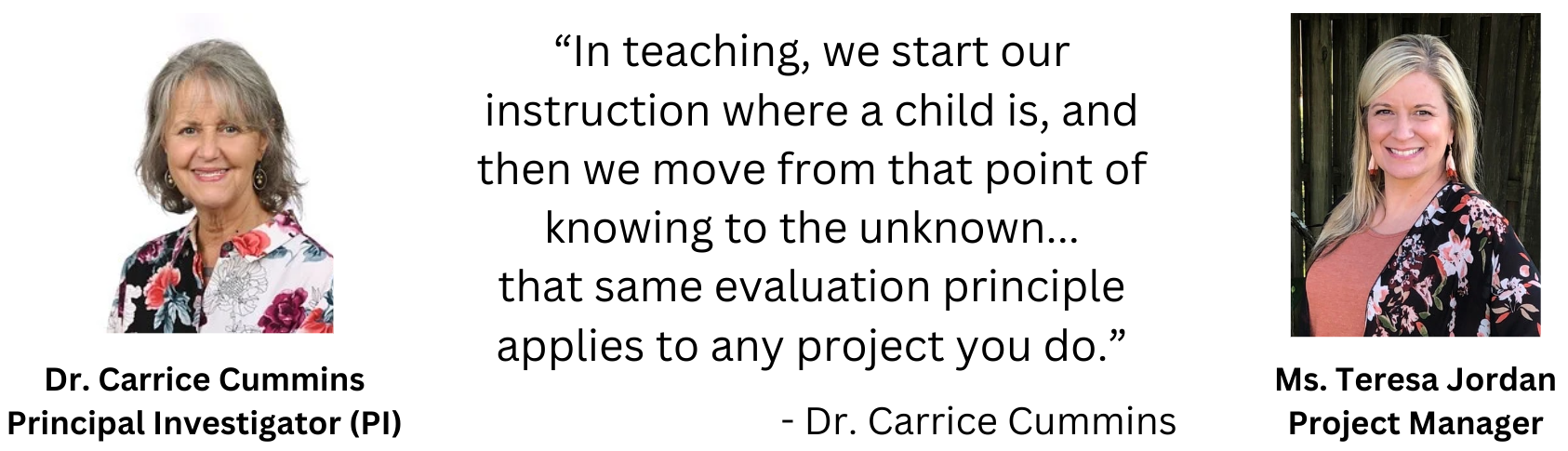

Kicking off the series with a real-life example of evaluation, I sat down with two recent clients to discuss their $4 million Science of Reading project at Louisiana Tech University. I had the honor of serving as the external evaluator for this project, which was the largest ever completed by the university’s College of Education and Human Sciences.

Welcome to our conversation.

Let’s start with a fun question before we dive into details. What are each of you most proud of about the Science of Reading project?

Dr. Cummins: There are a lot of things that I am proud of in relation to this project. One is the fact that we were able to pull so many people together, both internally and externally, to work together as a team. We were also able to forge some needed connections between higher education and the Louisiana State Department of Education, so that we are all working toward the same goal. And I guess in the bigger picture, the thing that I am most proud of is the fact that the project has the potential of huge impact. When we help teachers grow their content knowledge, the ultimate goal is impacting student learning across the state of Louisiana. So that would be my proudest moment, thinking that together with the Department of Education we have the opportunity to make that happen.

Ms. Jordan: I'm most proud of the impact the project has on our state’s young readers now and also for years to come. You know, reading is essential to success in any area. So if we're able to help educators deliver the content that will, in turn, help students with literary knowledge, then we are helping to set all students up for success in whatever field they choose to do. I'm also proud of the engaging format of the modules.

Yes, that is huge. Now, Dr. Cummins, you are the PI of this project. Can you share a little about your background and how you got put on this project, to help set some context?

Dr. Cummins: I've enjoyed 50 years of working in a profession I truly love and have had the opportunity of working in that profession from various positions and roles. I served 15 to 17 years in the classroom. I actually began in high school and then moved my way down working in the elementary grades. I had the privilege of teaching every grade in elementary school, but most of my time was spent with my love absolutely being first grade. Of course back when I first started that was where you really taught children to learn to read; that since moved down into kindergarten. Then I changed roles, serving the district as Title 1 Elementary Curriculum Supervisor and had the privilege of also serving as an elementary principal. Over the past 23 years, I have been in higher education.

So a lot of different roles and positions have helped me understand education in general. But the best thing has simply been that every single role still involved working with children. Even though the children may have grown as they moved into pre-service, or even in professional development with well seasoned experienced teachers, they all involve being in classrooms and working with children.

I have also been engaged in literacy education on an international level. I was on the Board of Directors for the International Reading Association (now the International Literacy Association) from 2003-2006 and then on the Executive Board from 2009-2012 serving as President in 2011-2012.

And how I got involved in the project - this was one of the few projects that I didn't have to seek myself. It simply started with a phone call from the State Department of Education. They had been awarded this wonderful grant and asked if I was interested in working with them to execute it. So that led to talking to my Dean and making sure that our university wanted to take this on, that we had the facilities and capabilities of doing it. They all agreed, and that's how it started.

Awesome. Okay, so let's talk about the project itself. What were the main deliverables of the project?

Dr. Cummins: Our wonderful modules. Twelve very content-rich online modules that would ensure all of the K-3 teachers throughout the state were working with a common base of knowledge. Starting with the old no Child Left Behind as our basis of knowledge, but then fine-tuning that into what we now know from the current research, better known as the Science of Reading. And then we tried to make that content knowledge as interactive and fun and engaging as possible.

Then fast forward to today. Can you see how many teachers are enrolled?

Dr. Cummins: Right now we have 1,550 teachers who are at some stage through the process of the modules. At Louisiana Tech University, it is also impacting our pre-service teachers. Our literacy professors have been using a lot of our content and have rearranged their courses to be more current with the content. So it's making an impact with people who will be doing their teaching residencies this coming year.

Yes, that's awesome. And then considering how many students each educator teaches in their lifetime, that impact is going to just multiply over the years. Wow.

This next question is for both of you. What made the project challenging?

Ms. Jordan: The most challenging part of this project was keeping up with all of the moving pieces. There were too many moving pieces that we could not even imagine when we sat down to try to map out what all this project would entail. But taking all those moving parts, both anticipated and unanticipated, and organizing them while keeping communication open between the team members was one of the biggest challenges. You didn't want two people working on the same thing, and then you also didn't want something not getting the attention it needed. So just basically keeping the communication open and pulling all of those little pieces together to form the big puzzle.

Dr. Cummins: For me, the first challenge really began with the uncertainty of what was needed and wanted. The State Department of Education had just received this funding, and the guidelines were not yet developed. Often there is a very specific list of guidelines that you have to follow, but this one was initially wide open. That freedom is a good thing in many ways, but it's also a major challenge when you're not sure that what you're doing and thinking will meet the expectations. This challenge was soon rectified as discussions led to firm expectations which then propelled the project forward.

And then another challenge was finding the right people to write each module. The people who had the content knowledge, but also people that others would recognize as having the content knowledge so that they went into the modules feeling like they were getting the right information. So finding experts who were interested in doing it and also had the time to provide the information was a major challenge. And then just keeping a timeline when you had that many different people with different things going on in their lives and all working on other projects. And then finally putting all the content together and keeping it unique so that every author's voice was heard, but also keeping it uniform in some way so the modules were easy for teachers to navigate.

Yes, that makes sense.

Okay, now I want to turn our conversation to talk about evaluation. Dr. Cummins, at some point during the project, you made a comment that “learning never stops.”

Knowing your extensive background in the education field, that comment was really profound to me. Can you talk more about how evaluation connects to learning?

Dr. Cummins: You're right. To me, learning never stops. Hopefully, we're all learning something every day, regardless of how old we are.

In teaching, we start our instruction where a child is, and then we move from that point of knowing to the unknown and trying to move them forward so they continue to add to their repertoire of knowledge. So in education, evaluation is the way that we find out where children are to start with, so we then know where to proceed from that point.

And so that same evaluation principle applies to any project you do. You have to determine where you are and where everyone else involved in the project is, and then move forward.

We used the notion of formative assessment constantly. One in a formal way with you helping us stop and rethink everything. But then even between our internal team meetings and our evaluation meetings, we were constantly saying, “What have we gotten done? What do we need to do? What do we need to go back and redo?” And so we were constantly using that new data, to eventually get us to where we needed to go. That's what made the project successful.

I love that. Now I want to talk about the nitty gritty of project management.

This evaluation was different because we weren't looking yet at impacts on teachers or students. My whole evaluation was on the process of creating the modules.

So Ms. Jordan, as Project Manager, can you describe your role and responsibilities on the Science of Reading project?

Ms. Jordan: Well, traditionally a project manager's job is to oversee and coordinate all the aspects of the project from beginning to end, making sure you're staying within a budget and that the deliverables are to the standards of the stakeholders within this project. I would say we use the meaning of team to the n-th degree. We all did project management in some sense of the word. So as far as my role, I helped with the budget, making sure that payments were made on time and to the right people for the right amounts, the contracts were done the right way, and getting them through the university’s system. I took on a lot of secretarial roles, which was my former job so it made sense for me to do those things.

And that was no small job - we counted 20 contracts created and over 200 payments processed throughout the whole project!

And yes, y'all were a great team, for sure.

What were the biggest lessons you learned through the project and that you are taking into new projects?

Ms. Jordan: To plan for the worst, but aim for the best. We should all learn from our mistakes; and there are some areas where maybe in the past, I wasn't as vigilant on documenting conversations with external contractors. Whereas now I'm asking, what exactly are they going to be doing? What exactly are the standards they're going to deliver? Let's make sure we're getting all of this in writing ahead of time, that we're all on the same page on what we expect them to do. So I think that probably was the biggest lesson that I've learned.

Yes, what a good lesson.

Well, the last question is for both of you. What advice would you give to other grant teams about working with an external evaluator?

Dr. Cummins: That one I could say a lot about. But I guess my biggest thing is to get to know your evaluator early. I enjoyed working with you, Alicia. I will be honest, I have not always felt that way with external evaluators. In other grants that I've worked with, I didn't really know who the person was until the end when all of a sudden they were pulling it all together and sharing the “report.” So it’s important to get to know your evaluator early on. And you made a point of doing that, Alicia.

I’d also say to other grant teams, be honest from the very beginning. Don't try to hide things or provide a right answer. Say “this is what's happening right now…” so you can truly build that rapport that facilitates a natural conversation. Because I think that is what helped you be a part of our team, Alicia, not someone outside and external coming in at the end and telling us what we did well or what we needed to improve on. You did understand the project from early on, and that helped you form your questions from a place of knowing. That made us push a little deeper to get what we needed.

So that’s my advice - know your evaluator, and involve them in the process so that you feel good about your results. Even when the results aren’t good, they are honest and will help you do a better job in the future.

Yes, I love that. And that’s the kind of client I want too. The kind who wants me involved, to be in formative conversations from the beginning. So thank you for being that!

Teresa, anything to add as advice to other grant teams?

Ms. Jordan: I tend to be more open than some people concerning struggles or obstacles we encounter. I think constructive criticism is very valuable for a team, and you can't get it if you're not being honest. But the person giving the constructive criticism, like Dr. Cummins said, needs to really understand how things work. And so it is important to get someone like you, Alicia, who can get in the middle of everything and understand how the project really works instead of just looking at it from the outside.

So true. Well, I appreciate y'all so much. Thank you again for your time today.

Dr. Cummins: Thank you, we have enjoyed working with you.

Want to know what a real evaluation report looks like?

Here’s an example! The Results Summary page of the Science of Reading project’s summative process evaluation report: